American View: Are domain border skirmishes worth fighting? Yes. Every time.

Where does the buck stop in your security program? In many cases, this can be operationally defined by identifying who will take the blame and suffer the consequences when something goes wrong. For example, imagine that your organisation attempts to install a multi-million pound ERP solution and after a year of work has nothing to show for it. Who would get the axe for turning a massive pile of capital into ash? The CIO who owns all the technology in the organisation? The CHRO who owns the business functions automated by the ERP platform? The MD of implementation who couldn’t make the new solution work? The VP of development who couldn’t mesh current business processes with the new platform’s software? Or would your CEO take the hit since they ultimately approved the project and supervised every function head involved in the fiasco?

This illustration shows why the (hopefully metaphorical) knives come out whenever Big Things go wrong in the boardroom. The more publicity a project received, the more that the business depended on the new tech to solve a problem, and the more money that was tossed at vendors beyond the original budget, the more likely it is that someone will need to be shoved into the wicker man and sacrificed to the “market.” Responsibility can thereby be defined as “he who ultimately serves as the lone scapegoat for everything that went wrong.

Personally, I think that’s a simplistic definition. Sure, it works as a way to understand internal corporate politics … I just don’t think it’s comprehensive enough to explain why leaders at all levels come to virtual fisticuffs when their missions and responsibilities come into conflict. Let me explain …

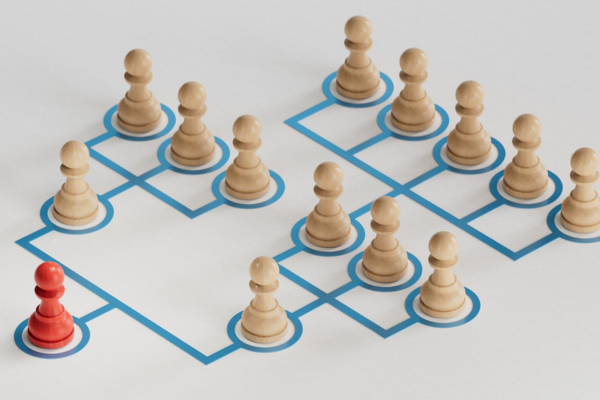

One of the essential factors of organisational behaviour in the late 20th century U.S. military was an obsession with “domains.” By this, I don’t mean the strategic war-fighting domain concepts (e.g., sea, land, air, and space). Rather, I’m referring to the hard limits of authority and “reach” that each operational function had in a unit. It didn’t matter if the unit was a battalion, brigade, division, or corps. Every officer at every echelon was obsessed with knowing the exact geography of their reach and the limits to their authority. Sure, a unit commander was ultimately responsible for everything their people did (and failed to do), but no unit commander ever could realistically supervise every discrete function performed within their unit. That’s why the hard lines of delegation based on specific operational domains existed.

For example, the S-1 shop in a battalion was responsible for all things related to personnel. That meant bringing in new soldiers, processing departures, overseeing leave, tracking payroll, and other functions pertaining to what a corpo would call Human Resources. The S-2 handled all things related to intelligence functions and, usually, sorted all the classified readiness reporting. The S-3 handled all operations planning and the the S-4 managed all logistics. Whenever you moved up an echelon, the S-1, -2, -3, and -4 became the G-1, -2, -3, and -4 but otherwise did the exact same things, just at a larger scale and with more personnel. Same for going up to division or corps where the G’s (for “general staff”) turned into J’s (for “joint staff”).

Every though these staff functions were well defined in regulations and procedures, the owners of each staff “shop” frequently butted heads. No matter where you were posted in the Army, S-3s and S-4s fought like jackals over who got to decide what got done and S-1s fought everyone for reasons that only they could understand. For example, the -3 might want to deploy 100 soldiers to Idaho but the -4 could block that plan because there wasn’t enough in the transportation budget. Or the -1 might want to send new replacements to fill empty positions in B company while the -3 demanded priority fills in D company because the latter was already tasked to go to a big training exercise. Conflicts arose when two staff officers couldn’t reach an acceptable compromise (which was almost always).

This long running soap opera got complicated once you factored in the staff sections’ “additional duty” assignments. For example, when I was assigned as the S-2 of 61st Medical Battalion, I was also tasked to be the 61st’s Information Management Officer because I was one of only a few people who knew how to build, maintain, and support computers. [1] This meant I was responsible for receiving all new tech from the S-4, then deploying it to each staff section at BN HQ, to every company, and to every detachment under the battalion’s authority. It also meant receiving, cataloguing, deploying, and installing software and training the users. It was an entire full-time job on top of my regular staff section work ‘cause that’s how the Army operates: if you’re not doing three different jobs as once, you’re a slacker.

Anyway, my work as the BN IMO meant I had some delegated authority from our BN Commander and from the next-higher IMO up at group level. If there was ever an argument with a company commander about how many PCs their unit got, my decision on the subject was final … even though the company commanders all outranked me. On the other hand, just because I was responsible for supporting the companies’ PCs, I couldn’t tell the owning commanders where to place them or demand access to them for patching or troubleshooting; the company commanders had total authority over all physical access to their facilities. If I needed to override a company commander’s decision, I’d have to convince our mutual battalion commander to pull rank. See above, re: soap opera. Tons of drama just to get a patch installed.

Conflicts like these served to define the operational boundaries between different functions, echelons, and process owners. There would always be conflicts as leaders tested the limits of their authority by approving or denying activities (sometimes just to see if they could). In the ensuing conflicts, there would always be some governing authority (e.g., the battalion commander) to judge all aggrieved parties’ arguments and set precedent for future conflicts by determining whose mission and domain took priority.

When I mustered off active duty, I discovered that corpo leaders were leery of setting operational boundaries for their formal suborganisations and informal cross-organisational functions. For example, if HR said that a new hire could start on Tuesday, but payroll said the new hire couldn’t start until their XYZ form was signed, who won? When would the new person start? These conflicts, I noticed, were rarely up-channeled to senior management for adjudication until something had gone so wrong that (a) business ground to a halt, (b) fines were assessed, and/or (c) reputational damage was inflicted. That is to say, domain borders and authority determinations would be ignored until they couldn’t be anymore.

I always suspected that this was because many MBA-holding senior leaders were only concerned with who ultimately takes all the blame when things go wrong. So long it wasn’t them, these folks were quite willing to play fast and loose with rules and regulations. Why sharply define and clearly communicate duties and responsibilities when doing so would only help point the finger of blame at who wrote and/or approved those standards? I get the intention even if I don’t agree with it. Self-serving ambiguity tends to work out great for the Yachting Class, but it’s frustrating as hell for people who work for a living. Without knowing whose word trumps all others, everything conflict quickly devolves into a melee.

This is why I’ve always been keen on clarifying the limits of my authority early on with my supervisors, MDs, VPs, and what-not. “You want me to do X, Y, and Z … What am I allowed to do to accomplish my tasks when there’s a conflict with another department or function owner? What am I not allowed to do? Who is my escalation authority? Are there special exceptions that I need to know about before inadvertently sparking a row over some rivalry that predated me?” This need to clearly define my operational boundaries goes hand in hand with my professional mantra “no responsibility without commensurate authority.” Said another way, if you’re not delegating me the power to make my mission happen, boss, then don’t blame me when things go pear-shaped. Either empower me to handle things or keep all that responsibility and take the blame yourself. You can’t have it both ways.

I’ve had higher-ups balk at my requests to clarify their intent. I understand that some (many, really) bosses are deeply uncomfortable both making decisions and accepting responsibilities for them. As a former squaddie, I can’t empathise. Sure, I get that you’re uncomfortable. That said, this is your bloody job! You’re getting paid a shedload more than me to make those decisions and to live with the fallout. Get after it! Draw your line in the sand and take whatever crap blows back as a learning experience. Do better next time.

Or, you know, you could empower your subordinates to take all those risks for you. Sure, that means they get the credit when it works out, but that’s a small price to pay … right?

On a day-to-day basis, I take great pains to respect the operational domains of others. It’s important to me that I don’t interfere with other’s functions and am careful to coordinate with rival domain owners before asking them to support something I’m doing. This “treat others as you want to be treated” approach has served me well. I believe strongly that leaders shouldn’t make enemies unless they absolutely must. Instead, offer support and deliver it cheerfully to cultivate allies and strengthen long-term relationships. Don’t get into unnecessary fights.

That said, there are going to be conflicts when domain boundaries overlap. Determining who has the superior claim is vitally important for setting future expectations and establishing precedent. When a rival function leader decides to encroach on my domain, I learned from the Army that they need to be sent reeling with a metaphorical bloodied nose to ensure they never dare try that stunt again. Then we reset: I respect your domain; you respect mine or get popped in the snoot, bucko. Make it clear that you’re easy to work with so long as you’re not messed with. In the long run, this leads to smoother interoperation, less drama, and less time wasted in executives’ offices.

I know that office politics can be distasteful. Offensive, even. That said, they’re often critical. Just like in the Army (where such conflicts were commonly derided as “[bleep] measuring contents”), sorting out who’s empowered to do what, when, and where is crucial for establishing clear and consistent delivery of vital services. It’s also important for preventing overlap. When two different suborgs start advertising that theirs is the only provider of Service X, mayhem ensues. Worst of all, it’s always the powerless line workers that take it in the neck when leaders play power games.

[1] It was a long time ago. The DOS days … ask your parents.

Keil Hubert

You may also like

Most Viewed

Winston House, 3rd Floor, Units 306-309, 2-4 Dollis Park, London, N3 1HF

23-29 Hendon Lane, London, N3 1RT

020 8349 4363

© 2025, Lyonsdown Limited. Business Reporter® is a registered trademark of Lyonsdown Ltd. VAT registration number: 830519543