The AI economy’s missing plumbing

Tim O’Reilly at O’Reilly Media argues that the AI debate is missing a critical piece: circulation. Innovation alone does not create prosperity unless value flows through jobs, wages, demand, and the real economy

The narrative from the AI labs is dazzling: build AGI, unlock astonishing productivity, and watch GDP surge. It’s a compelling vision, especially if you’re the one building or investing in the new thought machines. But it skips the part that makes an economy an economy: circulation.

An economy is not simply production. It is production matched to demand, and demand requires broadly distributed purchasing power. When we forget that, we rediscover an old truth the hard way: you can’t build a prosperous society that leaves most people on the sidelines.

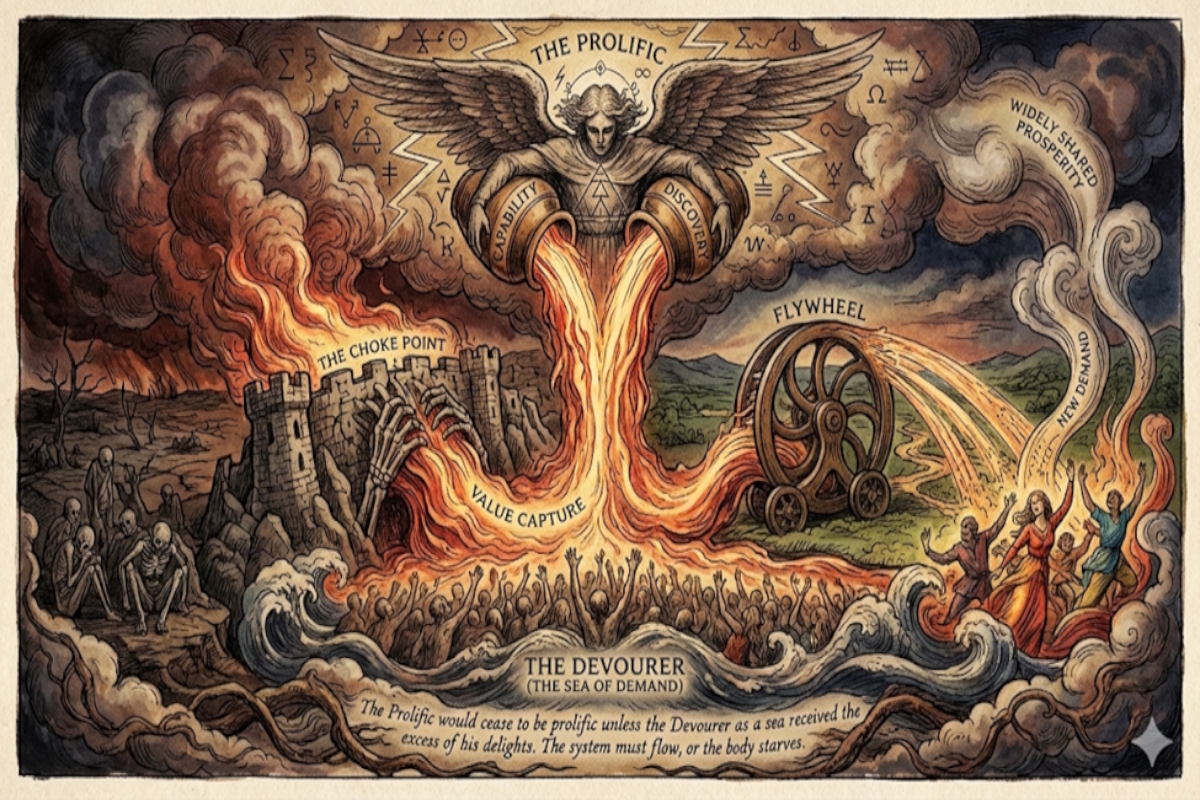

In The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, the visionary poet and painter William Blake (writing during the first industrial revolution) put the circulatory logic perfectly: “the Prolific would cease to be prolific unless the Devourer as a sea received the excess of his delights.” In other words: output has to be consumed. The system has to flow.

To achieve shared prosperity, we must not just ask “How smart will the models get?” but “How will the value circulate in the real economy of goods and services?” and “What new infrastructure and institutions are needed to turn capability into widely shared prosperity?”

The two dominant narratives, that AI creates value by automating the discovery of solutions to hard problems and creates efficiency by automating away jobs, are linked by diffusion.

Discovery alone is not the same thing as economic value, and it certainly isn’t the same thing as widely shared prosperity. Between discovery and economic value lies a long, failure-prone pipeline: productisation, validation, regulation, manufacturing, distribution, training, and maintenance. The valley of death is not a metaphor; it is a bureaucratic, technical, and financial landscape where many promising advances go to die. If AI accelerates discovery but doesn’t accelerate diffusion, we get headlines and paper wealth, but broad-based growth takes much longer to arrive.

The labour replacement theory of AI’s value presents an even sharper problem. We are told that AI will substitute for a great deal of intellectual work, much as machines replaced animal labour and much of human manual labour. Businesses will become more efficient. But who are the customers when a large number of humans are suddenly no longer gainfully employed?

This is not a rhetorical question. It is the central macroeconomic constraint that much of Silicon Valley prefers not to model. You can’t replace wages with cheap inference and expect the consumer economy to hum along unchanged. If the wage share falls fast enough, the economy may become less stable. The risk of social conflict and political backlash rises. Hopes that new jobs will be invented and vague handwaving at Universal Basic Income funded by the generosity of AI companies is not a winning strategy.

In a 2012 Harvard Business Review article, Michael Schrage asked a powerful question: “Who Do You Want Your Customers to Become?” His answer: “Successful companies have a vision of the customer future that matters every bit as much as their vision of their products.”

Great companies design for circulation. Henry Ford understood that his employees should be able to afford his products. Ford not only reduced the price of mass-produced cars but paid higher wages and reduced working hours, helping to invent what we now call the weekend, and with it, the leisure economy.

That’s not all. Mass adoption of cars required a vast extension of infrastructure: roads, traffic rules, hotels, parking, oil refineries, gas stations, repair shops, and the entire social reorganisation of distance. The technology mattered, but the complements made it an economy.

The early internet saw a similar dynamic. Google’s search strategy was rooted in a circular economy model. As Larry Page put it in 2004, “We want to get you out of Google and to the right place as fast as possible.” The company’s algorithms for both search and ad relevance were a real advance in market coordination and shared value creation. Economists like Hal Varian were brought in to design advertising models that were better not only for Google but for its customers. Google grew along with the web economy it helped to create, not at its expense.

Amazon’s Flywheel was also a mechanism design masterpiece for circulation: more users attract more suppliers with cheaper products, which attracts more users, creating a vast ecosystem of value for suppliers as well as for customers.

If AI labs wish to be architects of a prosperous future, they must work as hard on inventing the new economy’s circulatory system as they do on improving model capabilities. They need to measure success by diffusion, not just capability. They have to treat the labour transition as a core problem to be solved, not just studied. They have to be willing to win in the marketplace, not through artificial moats. That means committing to open interfaces, portability and interoperability. General-purpose capabilities should not become a private toll road.

Companies adopting AI face their own challenges. Simply using AI to slash costs and turbocharge profits is a kind of failure. The productivity dividend should show up for employees not as a pink slip but as some combination of higher pay, reduced hours, profit-sharing, and investment in retraining. Companies must use the AI opportunity to reinvent themselves by creating new kinds of value that people will be eager to pay for, not just trying to preserve what they have.

Governments and society as a whole need to invest in the complements that will shape the new AI economy. Diffusion will be limited not only by the fragility of our energy grid, by bottlenecks in the supply of rare earths, but also by sclerotic approval processes for new construction or the approval of new innovations.

Governments must also develop scenarios for a future in which taxes on labour might provide a much smaller part of their income. Solutions are not obvious, and transitions will be hard, but if we face a future where capital appreciation is abundant and labour income is scarce, perhaps it’s time to consider reducing taxes on labour and increasing capital gains taxes.

The choice we face is whether to build an economy that concentrates value, hollows out demand, and forces society into a reactive cycle of backlash and repair, or to build an AI economy that circulates, where discoveries diffuse, where productivity dividends translate into purchasing power and time, and where the complements are built fast enough that society becomes broadly more capable.

Tim O’Reilly is Founder, CEO and Chairman of O’Reilly Media

Main image generated with Gemini and Nano Banana Pro

Business Reporter Team

Most Viewed

Winston House, 3rd Floor, Units 306-309, 2-4 Dollis Park, London, N3 1HF

23-29 Hendon Lane, London, N3 1RT

020 8349 4363

© 2025, Lyonsdown Limited. Business Reporter® is a registered trademark of Lyonsdown Ltd. VAT registration number: 830519543